An embedded piece of city

The Tribeca site has been closed off to the public for 150 years. Out of sight, out of mind, it’s a place that’s had little meaning to surrounding communities. But this is about to change. Strategically located directly on the Regent’s Canal walk, near residential neighbourhoods and bustling centres of activity, Tribeca is set to become a key piece of the urban puzzle.

The Journal met with Daniel Kew, Associate Director for Bennetts Associates, to talk about the mission to bring Tribeca back to life as a well-loved and integrated piece of city. Daniel was the design lead for the project from competition stage to planning submission, leading on site strategy and architectural principles

The site has a rich industrial past, which has been eroded over time with more recent development. The Ugly Brown Building has become an emblem of an unloved part of North London. When you took on the project, what was your starting point to reinforce, or perhaps reinvent, the spirit of the place? Were there cues from the past that helped inform its new sense of identity?

Daniel: The site has a rich history, and it’s a history of dramatic change, which was driven by the industrial revolution and developments in transport and infrastructure. Historically, this land was quite bucolic with villas in natural landscapes on the edge of London. As the railways boomed, the expansion of London radically changed the area around King’s Cross and St Pancras, as well as the whole swathe of land to the north.

The existing building – a blank warehouse designed as a post office sorting facility – fills the site to the edges and doesn’t engage with the canal side character at all. It has a privatised strip of land alongside it that is completely unloved. This is a blank space on the public perception of the area, and it offers no opportunity for exploration. But it hasn’t always been like that. The original Bass Barrell warehouse, which burnt down in the 1970s, had a natural connection to the canal. Beer barrels were delivered via a railway bridge directly into the warehouse, where they were stored and later hoisted down onto barges for delivery around London.

There is a lot of interesting history here, but on the site, there are not many remnants left of those earlier uses, because the current scheme pushed that aside. So, we needed to rethink the way the site integrates with the city.

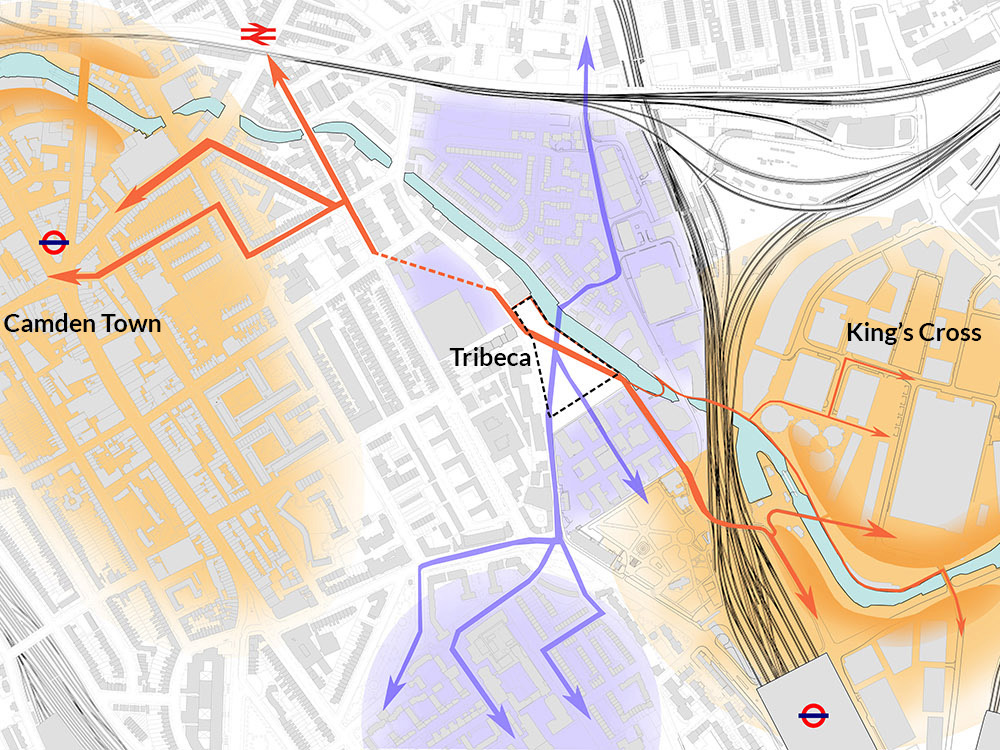

Tribeca sits at a critical hinging point between other neighbourhoods – King’s Cross, Camden and Somerstown – and aligns the Regent’s Canal walk, which extends 9 miles from Little Venice in the west to the Thames at Limehouse in the east. What has been the process of reconnecting Tribeca to the surround areas?

Daniel: One thing that is quite unusual about the site is that, even for London, is it highly multi-contextual: to the south are remnants of a workhouse as well as a functioning NHS tropical disease and medicine hospital; to the west is a series of mid-to-late 20th century buildings; on the other side of the canal is a low density 1980s housing area; and to the north we start moving into Camden and streets of Georgian terraces.

Trying to embed Tribeca into this diverse context was the primary focus. The site doesn’t have a clear identity and sense of place, so part of the job was to knit it into the surrounding established neighbourhoods, such as King’s Cross, Somerstown and Camden. We looked at the historic occupation patterns over time, which gave us a good indication of natural plot boundaries and desire lines. A proposed realignment of a previously consented footbridge will establish a route along the desire line between King’s Cross and Camden Town and allow the site to function as a linking piece.

We discovered that Regent’s Canal is probably the primary connecting feature in the area, and we really wanted to open up the site to the canal. The towpath on the opposite side is well used, so there is an opportunity to extend this activity to the Tribeca side. The buildings and open spaces are designed to offer glimpses into the central space from the canal as people pass by, which should make the place feel connected. That is so fundamental.

A lot of the key nodes and activities will also be connected to or focused on the canal. We imagine a future with barge activity and increased pedestrian flow brought about by the new bridge and the activity at the base of the buildings, creating a much richer experience for everyone.

Tribeca neighbours onto some of the most deprived wards in the city. How will the development benefit surrounding communities?

Daniel: This is really important and there are probably two key strands to this. One way is to knit this new piece of city into its context by opening up pedestrian connections, and the other is to provide a mix of uses. By establishing a genuinely mixed-use offer for the local and wider communities – a range and diversity of workspaces, retail, food and beverage offerings, as well as residential accommodation that includes 50% affordable – an all-day environment can be created, without dead times. This should promote natural movement patterns through the site, with people arriving throughout the day.

The spaces have been designed to be welcoming and lively, with a street-like character, characterful landscaping and thresholds that invite people in. We envisage morning coffee grabbers, families on the school run, workers arriving from the tube station, and mid-day lunch-timers from the workplaces, resting in the central square or walking between Camden and King’s Cross, stopping to rest under the trees. In the evening, post-work crowds would mix with visitors wandering along the canal, and diners that have been drawn in from the canal side restaurants. So hopefully, we have created quite an engaging offer that isn’t mono-cultural, that doesn’t have a single purpose, but that provides opportunities for the wider community to engage with the spaces at different times of the day, for different reasons.